Looking back on Liberty & Solidarity

Liberty & Solidarity, the political organisation of which I was a member, has recently disbanded. Consequently I think it is worth sharing some thoughts here on its successes and its failings.

Liberty & Solidarity, the political organisation of which I was a member, has recently disbanded. Consequently I think it is worth sharing some thoughts here on its successes and its failings.

I was a member of L&S for four years, from its founding conference where we adopted our constitution, to the this September’s, when we formally disbanded the organisation. During that period I was national secretary for two and a half years and also held the post of education secretary.

The Anarchist movement

Starting at the beginning, L&S very much came from the anarchist movement. All of those involved initially considered themselves anarchists and the project at that time was to build a “platformist” anarchist organisation. From the off however we did things a little differently from our sister organisations in Anarkismo, the platformist anarchist international grouping.

For starters, though far more common even just four years ago than it is today, we refused to follow the standard leftist model and produce propaganda paper. We felt that such initiatives tended to largely be a waste of time, with small print runs and little by way of tangible results.

Similarly, and scandalously to some in the anarchist movement, we tried to avoid political labels, preferring instead to describe what we actually believed, rather than whichever “ism” might be appropriately assigned to us.

Our relationship with the anarchist movement proved to be a difficult one. Because of several L&S members having split from the AF not long prior to the foundation of L&S there was already much bad blood, and L&S’ political trajectory, moving us away from the anarchist movement, did not help matters. Perhaps it would have been better if we had made a clean break at that early stage, however at that point in time we still thought of ourselves as anarchists, even if the rest of the anarchist movement didn’t agree with us.

Our reputation in the anarchist movement was also tarnished by some cock-ups on our part, including some less than diplomatic behaviour from our own members. The blame for poor relations does not rest squarely on the shoulders of L&S however, the sectarianism of the anarchist movement meant that our organisation was soon the subject of various conspiracy theories which went largely unchallenged. In part this was to do with the closed nature of L&S, with our internal discussions kept private by our members. On reflection I think it would have served us well to have been more open and had more of our discussions in public, but given the attacks being directed at us from the anarchist movement the instinct to batten down the hatches was an understandable one.

We took the decision to take little heed as to what the anarchist movement thought, after all, 99.9% of the working class weren’t anarchist, so why should we care what this tiny minority thought? The problem however was that we were still in many ways part of the anarchist movement. For some branches the anarchist social scene was still the norm, and even where this wasn’t the case, the largely anarchist dominated IWW was the prime focus of our industrial strategy.

Industrial strategy

Many L&Sers had first met each other through involvement in the IWW and indeed it was the shared project of the IWW that strategically united L&S for the first couple of years. Initially we were concerned with helping win an international delegates convention so that the UK section of the IWW would have fairer representation. This process involved conflict with corrupt bureaucrats such as Jon Bekken and his Philadelphia IWW cohorts.

Whilst the delegates convention was being won we also wanted to play our part in growing the IWW domestically. The IWW had adopted as its official strategy a focus on building the union as a dual card union in the health industry. We eagerly set to work on this, doing our best to assist IWW blood service workers in their fight to stop blood centre closures.

In a bid to support our strategy many L&S members got jobs in healthcare and most wound up in UNISON, the largest healthcare union. As part of our work within the mainstream labour movement we also participated in the National Shop Stewards Network and helped initiate the NSSN syndicalists grouping within it.

Our participation in the NSSN however proved sadly short lived. Sectarianism from the Socialist Party who held a majority on its executive meant that the network was soon forced to split, leaving the NSSN a shallow SP front. In retrospect splitting at this point may have been a mistake, it certainly left us out in the wilderness in terms of our industrial strategy, with progress in growing the IWW as a base union slow to nonexistent. We had also failed to grow our influence in the IWW, being regarded with suspicion by the majority of IWW activists due to our bad relations within the anarchist movement.

Internal organisation

Our platformist roots showed most prominently in our constitution, which started out life as a copy of that of the WSM, our Irish sister group. Reacting to the structurelessness and disorganisation of the anarchist movement from which we had come we were keen to ensure that we had a well structured and democratic organisation. The organisation was to be composed only of those who were active in pursuing one or both of our dual strategies, workplace or community organising.

This allowed us to experiment with new ways of organising ourselves. We implemented “battle plans” for branches and disparate members, which were to be derived from an overall national battle plan. These plans consisted of SMART targets to be achieved over the next year, this way we could monitor our own progress. This approached forced us to think strategically in the near term, about what we wanted to see and what we thought was realistic to achieve within one year. Unfortunately we never quite managed to get the system working properly. Part of the issue was that politics is obviously unpredictable, a more flexible planning mechanism better able to cope with the unforeseen might have been more implementable.

Another good idea that didn’t quite work out was the decision we took early on to concentrate on growing through the “mass organisations”, the unions and community groups we were involved in, rather than through recruiting from the anarchist movement. Sadly recruitment was something we never managed in great numbers, with most of our new recruits coming from the anarchist movement in spite of our decision to look away from it. Partly I think the issue was it was a rather big jump, from being a trade union member to joining a disciplined political organisation. Some broader interim organisation would have been useful to enable potential recruits to politically develop and to allow us to work with allies who perhaps might never join our organisation.

Our failure to recruit meant that the organisation stayed roughly the same size, with structures like branches proving difficult to maintain and less useful with fewer members. This resulted in L&S becoming something of a burden rather than a help to its members, with smaller branches seeming somewhat pointless. Nationally the organisation had been useful at coordinating our work within the union movement, but when we lost direction in this arena after our withdrawal from the NSSN this left the organisation with less purpose. On the community side of things this had always been a more disparate form of activity less likely to benefit from a national organisation.

Our concern that the organisation was becoming a burden rather than a useful tool stemmed from our now syndicalist perspective that a political organisation was only valuable in so far as it helped strengthen and influence working class organisation. Rightly, we always prioritised this goal over building our own group.

In the end though we decided to disband the organisation we also concluded that we still held a lot of shared ground. Hopefully in the coming years former L&S members will stay in touch and work together for our still common goal; the elevation of the working class to power in society.

Are you a campaigner or an organiser?

Most people reading this blog will have participated in some form of political campaign. Indeed campaigns, whether to save the local library or earn workers a living wage, are the bread and butter of left wing activism. Sometimes these campaigns are won, sometimes lost. Sometimes, all too often in fact, we find ourselves having to fight the same campaign all over again. Clearly there are many factors that determine the fate of a campaign but crucially only some of those factors are within our power to alter.

Most people reading this blog will have participated in some form of political campaign. Indeed campaigns, whether to save the local library or earn workers a living wage, are the bread and butter of left wing activism. Sometimes these campaigns are won, sometimes lost. Sometimes, all too often in fact, we find ourselves having to fight the same campaign all over again. Clearly there are many factors that determine the fate of a campaign but crucially only some of those factors are within our power to alter.

Any campaign is made up of the same basic ingredients, popular participation, finance, activists etcetera. The degree to which a campaign is well funded, its ability to mobilise people and its shrewdness of tactics all have a concrete effect on its outcome. Most campaigns, whilst often run by seasoned campaigners, find themselves starting from scratch with regards to much of this. A bank account must be set up and funds raised to populate it. Activists must be trained in various skills or learn on the job how to manage the media, build demonstrations and negotiate with officials. Contacts lists must be built and websites must be created.

Naturally these many tasks are time consuming and the better each is performed the more likely the campaign to win. This is why an organising approach, where individual campaigns are used to build longer-term organisation, can yield far better results. At the conclusion of any campaign the wealth of experience, knowledge, contacts and finance that has been accumulated typically disappears. Using campaigns to build permanent organisations such as unions or tenants groups allows campaigners to consolidate the power wrought by their campaign, and gives a stronger base for future victories.

Permanent organisations can also enable more than immediate victories. When a campaign is won the confidence of those in it and indeed all those who witness it that they too can make positive social change grows. This confidence can easily dissipate though, without structures in place to nurture and strengthen it. The left doesn’t have access to mass media to get our message out there, so our strategy must be asymmetric, using organisations to communicate with members brought in through campaigns. In this way we can consolidate the confidence of participants and solidify it into a general culture of fighting back.

But culture and willingness is only one aspect of out capacity to fight and win. Power, our ability to effect the course of events, is ultimately derived from how organised we are. By being able to train activists between campaigns, provide serious finance and to maintain contact networks, organisations like trade unions have real power should they choose to wield it.

Looking at campaigns and organisations is of course only looking at one side of the equation. In examining why campaigns fail or succeed we also need to examine why it is we find ourselves continually fighting them. The answer, ultimately, has to be the capitalist system, who’s relentless drive for profits at the expense of all else wreaks destruction on our communities and workplaces. But just as individual campaigns address individual symptoms of this underlying problem, opposition to capitalism can only oppose the symptoms, the excesses of this system.

This is because opposition in and of itself provides no alternative. To this day there has been only one coherent alternative presented: socialism. Socialism proposes tackling capitalism at its roots, in the economy which generates its vast profits. By bring the economy under the control of the general populace (socialising the means of production to use the Marxist lingo) the capitalists are stripped of their source of power and wealth. In short, the only way to rid ourselves of capitalism is to bring about socialism.

The pursuit of socialism, the winning of individual campaigns and the building of powerful organisations all fit naturally together. Any genuinely mass organisation must campaign and win for its members or it will decline, examples of this are only too common. Individual campaigns , on the other hand, that do not serve to build organisations, risk squandering their resources and experience come victory or defeat. Ultimately, socialist or not, we need to make ourselves organisers rather than campaigners, building long-term capacity to win and win again.

Class warfare

Class war is a concept immediately familiar to most those on the far left and indeed is sufficiently well known as to receive the occasional reference in the mainstream media. As with all concepts we use to understand social forces, it colours how we think about our political activity and influences how we act day by day. Consequently is worth re-examining to tease out our understanding and see how such concepts can be usefully applied and extended.

Class war is a concept immediately familiar to most those on the far left and indeed is sufficiently well known as to receive the occasional reference in the mainstream media. As with all concepts we use to understand social forces, it colours how we think about our political activity and influences how we act day by day. Consequently is worth re-examining to tease out our understanding and see how such concepts can be usefully applied and extended.

Clearly, with the irreconcilable differences in interest between workers and bosses there is indeed constant conflict. Comparatively small strikes and other workplace based actions constitute a continual guerrilla warfare between workers and bosses. However recently this class struggle has perhaps been more akin to a cold rather than hot war, with low-level fights breaking out at the peripheries. At no time recently has the capitalist class felt particularly threatened by organised labour. The main armies (on our side the unions) have seldom thrown themselves in to full battle with capital, after all they are not ideologically predisposed to.

Some on the left have sought to counterpoise themselves to this ideologically-induced passivity by elevating unrelenting warfare to a cast iron principle, believing that the correct response is always to strike, always to ratchet up militancy. The folly of this stance is of course that much like in real warfare there are times when an orderly retreat is better than risking a total rout. Striking after the harvest is in is going to be far less effective than waiting 9 months to when your labour is at its most needed.

Of course this sensible stance can lead to leftists and union activists to put themselves in odd positions. If some hot-head wants to call a strike the day after the harvest is in any sensible revolutionary would do their best to contradict them, to argue against striking. Similarly there are times when we have to advocate reaching agreements with our bosses, armistices in the class war, as our meagre resources do not permit us to fight on all sides simultaneously. As much as such compromises may be distasteful to those who prefer to preach from an ivory tower, no revolution will ever be made without someone getting their hands dirty.

“Amateurs study strategy; professionals study logistics” goes an old military adage, one which can also be applied to the class warfare analog. In our context strategy can be seen as the grand plan, how we intend to win a given confrontation with the government. Logistics then is the ability to set up the context of a battle, the ability to mobilise resources that serve to establish the strategic context in which a battle will be fought.

In regular warfare logistics is hugely important. To pick just two prominent examples, the Ho Chi Minh trail was key to the victory of the Viet-cong by enabling them to swiftly move supplied to the front. Similarly the Prussian railways proved a decisive factor in their victory in the Franco-Prussian war.

Our equivalent has to be our own war machines, our mass organisations. Where we are well funded and well organised, where our members are well trained and closely linked in with the rest of the union, we will win. We need to build the sort of organisations that are optimised for victory and designed to build and consolidate based on them. In practice this means that in addition to maintaining a solid administrative base we also need to be at the forefront of developing training and encourage intra-union socialising.

In order to ensure the organisational cohesion systemic planning necessary for our war machines, much like a regular army we need a unified command. At present coordination between unions is rare and ad-hoc. Rivalries between unions are often intense and frequently there will be a multitude of unions competing to organise one industry or even one workplace. If we are serious about building unions as fighting machines, capable ultimately of transforming society, then we need to argue for mergers, for organisation on an industrial basis and for extending unions across borders. In short, we need One Big Union.

In summary, I think looking at class struggle as analogous to military warfare is a largely useful concept. The metaphor can be extended in several ways to suggest to us areas of importance and we can learn much from the great lessons of military history, whether it be the importance of logistics, the necessity of a unified command or the importance of a well ordered retreat.

Concentrating our forces

The left is undeniably weak. Compared to our capitalist adversaries we have little in the way of finance and none of our organisations are as powerful or organised as the state. We need to be able to punch above our weight, and to increase our capacity so that eventually our resources enable us to force lasting social change.

So how can we ensure we get maximum bang for our activist buck? An obvious response is to concentrate our meagre forces so that our combined focus and strategy allows us to win things we would not usually be able to. The opposite of this, a scatter-shot approach, frequently results in resources being spread too thinly and consequently failing to make an impact.

In order to counter this we need to prioritise where we spend our time and money. Clearly there is a myriad of activities which can aid the socialist cause so we need to be quite picky in deciding what our priorities are. Of course in marking something as a priority it is implicit that other activities will be deprioritised. Sometimes this will mean hard choices, but if we aren’t willing to be hard-headed then we can’t expect our movement to get far.

Applying this logic more broadly we should be looking for a systemic solution to the underlying cause of many of the world’s ills; capitalism. This might mean that sometimes in our bid to fix this underlying problem we don’t go to the most oppressed first. We ought to more strategic and look at how our immediate actions can contribute to changing capitalism, rather than healing its symptoms. In order to help us make these decisions we need some criteria, how can we tell a priority from something less important? One approach is to help those who are most in need, to find the most oppressed and attempt to improve their conditions. Taking this moral approach to its logical conclusion often leads us down the road of simple charity. If workers are being paid badly we want to organise them to allow them to demand better wages, not give them some of our own money to alleviate their immediate plight. In short we look for systemic solutions to underlying problems, in this case a group of workers lack of collective power.

That said, it is worth noting that in order to bring about lasting social change we need to have the majority of the populace on our side. In order to achieve that we will need to demonstrate that collective action can improve peoples lives in the hear and now. Whilst looking at what will provide the best challenge to capitalism should be regarded as most important, frequently this will also coincide with aiding those in need.

In addition to looking at the effectiveness of our actions in contributing to the bigger picture, we also need to have an eye out for what will grow our own capacity. Organising workers not only allows us to remedy an immediate injustice and increase confidence in the effectiveness of collective action, but it also allows us to build on that workplace organisation, encouraging those organised to get involved elsewhere in the movement.

In summary, concentrating our forces is hugely important if the left is to punch above its weight and stand a chance of winning lasting social change. This involves being hard-headed about what is most effective and is best to build our capacity. This needn’t be completely heartless however as what is most effective will often also be activity that sees us aiding our fellow workers in improving their lives.

A brief history of Syndicalism (part 2)

Whilst never explicitly syndicalist the Industrial Workers of the World, founded in 1905 in Chicago, clearly had a lot in common with their syndicalist comrades elsewhere around the globe. The primary instigator in this new union was the Western Federation of Miners, a highly militant industrial union. The WFM sought an alliance with various socialist organisations and smaller unions to create a national union body outside of the craft-focussed American Federation of Labour. The AFL represented craft-unionism par excellence, its member bodies being forcibly split along craft lines on pain of expulsion.

In contrast to this divisive stance the IWW not only advocated industrial unionism but that there should be one union for the whole of the working class. After all, they all ultimately had the same interests. Somewhat optimistically the IWW saw itself as the basis for this One Big Union and this positioning often lead to an antagonistic relationship with the far larger AFL.

In spite of its isolation from the mainstream of the labour movement the IWW mounted many inspiring organising campaigns, the most famous of which was undoubtedly the Lawrence textile strike. Over 20,000 workers walked out on strike and chose the IWW as their union. The strike was ultimately won and elevated the IWW to the status of household name.

Sadly, in spite of its new national profile, the IWW failed to consolidate its success and within a couple of years the IWW was back to a token presence in Lawrence. This pattern was seemingly replicated across many IWW organising drives, with the organisation continually struggling to maintain a stable membership, even though it managed to win many spectacular victories.

The sole exception to this trend proved to be the Marine Transport Workers union, based on the docks in Philadelphia. This union was to prove stable and lasted for a good 10 years before a large section left the IWW as the result of a political split within the organisation.

Sadly, said split was not an isolated incidence, the IWW suffered numerous damaging splits throughout its history. The first of these was at its second conference in 1906! The IWW managed to grow in spite of both these splits and of brutal oppression, up until around 1923, where yet another split acted as a catalyst for a decline from which the union has never recovered.

One of the most interesting splits from the IWW was that lead by William Z Foster, who in 1912 formed the Syndicalist League of North America. The league’s inspiration had come from the CGT in France and Foster was convinced that as in France syndicalist should work within the mainstream trade unions. In the years after he left the IWW Foster found himself the leader of the spectacular “great steel strike”, involving over 100,000 steel workers. Though the SLNA did not outlast the first world war Foster continued his work within the AFL through the Trade Union Education League which was associated with the newly founded Communist Party. Sadly as happened in Britain and France the cancer of Stalinism slowly replaced syndicalism within the left of the trade union movement. The Comintern eventually forced the TUEL to split from the AFL, resulting in a swift deterioration in the organisation.

And everywhere else…

Syndicalism however wasnt confied to France, Britain and the USA. There are plenty of other important syndicalist unions, such as the USI in Italy who’s activists were instrumental in the famous workplace occupation and factory committee movement. The most well known syndicalist union is probably the famously anarchist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo whose millions of members fought Franco’s fascists in the Spanish civil war. What many don’t know however is that the CNT for much of its life was not an anarchist union, it was a syndicalist union along the lines of the CGT or IWW.

Irish Transport and General Workers Union is another great example of the importance of building unions as social insitutions. The ITGWU in its heyday was the most powerful union in Ireland and bought over a country estate outside Dublin for use for union picnics and other social activities. The union’s syndicalist influence clearly derives from the likes of James Conolly who was one of its key organisers and who previously worked for the IWW in the United States.

Syndicalists today can learn a great deal from all of these unions. Whether its the importance of the union as a deeply rooted social institution or the need for membership stability there are clearly lessons to be learned. Whilst I don’t presently feel qualified to discuss Syndiclaism outside of France, Britain and the US hopefully this small snapshot will prove useful, I intend to add to it with further national examples as I read more.

Read part one here.

This post was originally part of an educational presentation entitled “Syndicalism then & now” I made for Liberty & Solidarity.

A brief history of Syndicalism (part 1)

It started in France

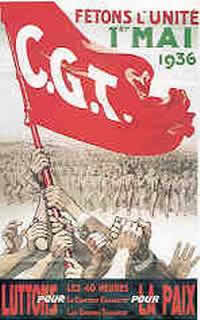

The Confédération générale du travail, formed in 1895 in France, is widely regarded as the grandfather of the syndicalist movement. Within its ranks socialists alienated by party politics, radical republicans and anarchists joined forces to forge a new movement; revolutionary syndicalism. In a short space of time syndicalist ideas came to dominate the CGT, at the time the only sizeable union in France.

This dominance was reflected by the Charte d’Amiens, a declaration of syndicalist principles adopted by the confederation in 1906. It asserted the political independence of the CGT from all parties:

as far as it concerns individuals, the Congress asserts the complete freedom for union member to participate — outside of his corporate grouping — in those forms of struggle that correspond to his philosophical or political concepts, limiting itself to asking him in exchange to not introduce into the union the opinions he professes outside it.

Around this time the CGT was at the centre of the campaign for the eight hour day in France. This campaign provoked much industrial unrest and triggered the spectacle of a “socialist” parliamentarian (and erstwhile proponent of the general strike!) ordering troops to fire on strikers. The CGT used tactics pioneered in the early days by leaders such as Émile Pouget who advocated the use of sabotage to aid strikes and stop scabs.

The true strength of the CGT however lay not in such tactics but in the solid basis it had within working class communities. This strength flowed from organs known as the Bourse du Travail which brought together unionists in a given town to provide services for the working people which the state did not. This encouraged workers to socialise together around the union and rendered it a powerful social institution.

The syndicalist’s dominance of the CGT ended with the beginning of world war one. The anarchist Leon Jouhaux and his supporters on the union’s executive lined the union up with the French state in the infamous union sacrée. Syndicalists throughout the CGT attempted to reverse the betrayal, opposing it on the executive and attempting to call a congress to deal with the matter, however they were outmanoeuvred.

After the war and in the wake of the Russian revolution the syndicalists attempted to regain hegemony within the CGT. They formed the Comités syndicalistes révolutionnaires and by the end of 1921 had succeeded in winning almost half of the CGT back to revolutionary syndicalism. It was at this point however that pressure both from those wanting to join the communist Profintern and the anarchists combined to force a split, the revolutionary syndicalists forming the Confédération générale du travail unitaire.

Eventually in 1936 the CGTU and CGT merged, however by this time syndicalist influence had waned, replaced largely by the stalinism of the Parti communiste français. After further splintering of the trade union movement later in the century, the CGT is still to this day the largest union in France. On paper it is still committed to the Charte d’Amiens and a refounded Comités syndicalistes révolutionnaires works within its ranks to once again win it to revolutionary syndicalism.

Syndicalism spreads to Britain

In the UK the syndicalist movement was kick started in 1910 by veteran trade unionist and socialist Tom Mann, who had visited France and was impressed by the model of the CGT. Much like the revolutionaries in France he adopted the approach of working within the existing unions, forming the Industrial Syndicalist Education League to propagandise for syndicalism.

During this time Mann lead the successful 1911 Liverpool transport strike. After the strike he was imprisoned for having published a leaflet during the course of the strike urging troops not to fire on strikers. This imprisonment brought him and the fledgling ISEL great attention and the ISEL’s newspaper The Syndicalist reached a circulation of 20,000.

A broader syndicalist movement out with the ISEL also flourished after Mann’s imprisonment. In 1912 the Miner’s next step, a pamphlet arguing that the miners must go beyond nationalisation and argue for workers control of their workplaces appeared in the coalfields of south wales. The Daily Herald, a distant ancestor of todays Sun was also founded in 1912, the paper was hugely sympathetic to the syndicalists and its readers groups up and down the country became hives of syndicalist debate and practice.

Sadly in spite of this strong movement the ISEL came to a premature end in the 1913-14, when the organisation was seized by “dual unionists” who favoured splitting from the existing labour movement to set up new unions. Though this was the end of the UK’s primary syndicalist organisation its influence was felt in coming decades, as the syndicalist influenced Socialist Labour Party helped organise munition worker strikes during the first world war, leading to the formation of workers committees across the country and the famous “red clydeside” period.

Syndicalist inspired politics also found a home in the early british communist party, many former members of the ISELincluding Mann filling its ranks and working within its “minority movement” within the TUC unions.

Part two is available here.

This post was originally part of an educational presentation entitled “Syndicalism then & now” I made for Liberty & Solidarity,

What is syndicalism?

Syndicalism is the belief that workers should run their own workplaces some that they may be administered effectively and democratically. Through this workplace control, exercised nationally via labour unions, workers could wield democratic control over the whole economy. Labour unions are key to this idea as they have the potential to organise and socialise large numbers of workers together, on the basis of fighting for their collective interests and to increase their collective power in the workplace.

Syndicalism is the belief that workers should run their own workplaces some that they may be administered effectively and democratically. Through this workplace control, exercised nationally via labour unions, workers could wield democratic control over the whole economy. Labour unions are key to this idea as they have the potential to organise and socialise large numbers of workers together, on the basis of fighting for their collective interests and to increase their collective power in the workplace.

But as syndicalists would be the first to admit that the labour unions of today are not up to the lofty task of winning democratic control over the economy. Consequently syndicalists propose numerous ideas for building unions to the point where they can take power in workplaces.

Syndicalism as a form of socialism has always emphasised the importance of the “economic” that is the bread and butter workplace demands of pay and conditions, over the “political”, the battles of ideologies and party politics. This is because we observe the politics can be a hugely destructive force and tying a labour union to a particular political creed is likely to lead to the exclusion of those who are not adherents of said creed.

That said clearly socialism is a “political” concept, but ultimately this political conclusion flows naturally from the strengthening of unions and workers being exposed through struggle to the class nature of society and their own collective power.

Syndicalism is also associated with militant action, with syndicalists playing key roles in major strikes, for example during the great unrest period before the first world war. However, syndicalists willingness to use militancy to gain results is not an aesthetic preference, militancy for militancy sake can be destructive, it is important to apply militancy only when it is the best strategy to win.

Another key concept often associated with syndicalism is industrial unionism, though it is worth noting that historically there have been some syndicalists who have rejected industrial unionism.

Industrial unionism is where unions structure themselves around the supply chains of industries. For example this might mean that retail workers in a shop would be in the same union as the workers in the distribution centre and the farmers growing the food. This means that when the retail workers strike they are more likely to incur solidarity from their fellow union members elsewhere in the supply chain and so stand a much greater chance in being able to shut the entire proccess down and render scabs useless.

In contrast to this approach stands the tradition of craft unionism, where workers are broken up not on the basis of their industry but on what trade or craft that worker practices. This approach has proved hugely damaging, frequently pitting “skilled” against “unskilled” workers in battles for relative privilege rather than uniting workers in a way that renders them powerful.

This divisive form of unionism is still in evidence today with the most prominent example in the UK being the education sector. In a typical university there will be at least four different unions, one for the janitors, one for the cleaners, one for the technicians and one for the lecturers (who couldn’t possibly let the smelly little plebs into their union). This concretely weakens the power of even the more privileged lecturers as should they strike they cannot count on the janitors to strike with them, a move which would force most buildings on a campus to close completely.

Clearly, ideas like industrial unionism and syndicalism are as relevant today as in the heyday 100 years ago. In order to understand how we can best apply syndicalist ideas today, we ought to look at how syndicalist have fared historically, this will be the subject of my next post.

This post was originally part of an educational presentation entitled “Syndicalism then & now” I made for Liberty & Solidarity, I intend to post a couple of other posts adapted from other portions of this presentation on the history of syndicalism internationally and what a new, up-to-date form of syndicalism might look like.

Strength in the union

Unions have forever been a socialists friend, often at the centre of exciting periods of revolutionary activity such as Red Clydeside or the Spanish revolution. However today’s unions seem a far cry from the revolutionary militancy of yesteryear and so it is worth asking the question, why should socialists and radicals today care about unions?

One reason to care is numbers. At 6.5 million members the trade union movement is the largest organised body of the working class in existence. What’s more the trade unions constituency incorporates nearly the entirety of our class, as being a worker is an experience, unlike going to university for example, which almost all of us will share. Now clearly size alone wont cut, after all the largest political party is the labour party and most of the socialist left is to be found (quite rightly) outside of it, but the sheer capacity of the unions must be acknowledged.

This capacity is at its greatest when trade unions mobilise their members collectively to improve their lot. Such a mass experience of collective action, and hopefully a collective victory can not only serve as the basis for further strengthening the organisation and power of our class but also carries within it the seeds of our new society.

If or future society is to be a collective, socialistic one, it should follow that bringing it about must also be a collective effort. Were socialism to be installed by coup or some other individualistic, minority-based strategy then you would expect to find any new collective structures swiftly being corrupted or abandoned as has been borne out by various historical examples. This is partly because people are creatures of habit, and are not very good at going outside their comfort zones. If people have not been socialised into collective ways of working, if they have not experienced for themselves the possible pitfalls such as corruption and how best to deal with them, then it would seem that any collective experiment is doomed to failure. Consequently it would seem that the processes of attaining socialism must in itself be collective and socialistic, building the new world in the shell of the old.

Trade unions can serve to facilitate this collectivism but they can also play an important role in the building process. A revolutionary change in society, especially one involving massive numbers of people is difficult to pull off. It needs organisation and the self-confidence of all those involved. Through building up organisational size and capacity through small victories, increasing the confidence of the members and the reputation of the union bit by bit we have the potential to create powerful fighting machines, just like the unions of yesteryear.

Sadly as we all know unions are presently ill-suited to this task. Density is in decline and the sort of union activity that builds confidence and wins victories is seemingly rare. What’s more large sections of the population, especially young casualised workers have never had any experience of trade unionism. Clearly these workers need to be organised, need to be part of our collective solution to the problems of capitalism, and so the question is then, how is this best achieved?

Ultimately this is a tactical decision. Some, such as the IWW, advocate setting up new radical labour unions and this approach has met with a limited degree of success, for example organising Starbucks workers. Other socialists, noting the huge capacity of the existing movement, feel its better to intervene within those unions that exist and argue for them to extend unionisation to those whom it is presently unavailable.

There are arguments for either approach, what is clear is that one way or another collective action and organisation must be extended to the entirety of the working class. This is why as a socialist I have been drawn towards syndicalism, with its focus on the potential of labour unions as transformative agents in society. But whichever socialist creed you adhere to we should acknowledge that unions, though frequently inadequate and inaccessible, have the potential to play a huge role in changing society for the better.

Some ideas for union renewal

In order to create a better world we, the working class, need power. Such power can only come through collective organisation around the one thing that unites all members of our class – work. But trade unions, the bodies with which we socialists attempt to create such collective organisation, are in decline. If we are serious about building trade unions and winning them to socialist ideas then we need to come to the table with ideas of how to reverse this downward trend.

In order to create a better world we, the working class, need power. Such power can only come through collective organisation around the one thing that unites all members of our class – work. But trade unions, the bodies with which we socialists attempt to create such collective organisation, are in decline. If we are serious about building trade unions and winning them to socialist ideas then we need to come to the table with ideas of how to reverse this downward trend.

The traditional left wing approach has often been to argue for greater militancy, an approach which has been discussed elsewhere on this blog. However there are other less obvious but perhaps even more important possibilities for trade union renewal.

Recruit or organise?

One of the obvious places to look for ideas for union renewal is the few success cases of today. One of the few unions that has grown substantially in the past 10 years is the American behemoth the SEIU. over the past decade it has succeeded in nearly doubling its membership to a staggering 2.1 million. This has been in spite of the incredibly hostile conditions of industrial relations within the USA.

So how did the SEIU achieve this against-the-odds success? It looked to the Australian movement the organising methodology it had adopted to raise its own membership figures, the organising model. Now both the left and the trade union movement in the UK like to talk about organising. For the trade unions “organising” often simply means recruitment, handing out union membership forms, whilst for the far left “organising” only really seems to translate as party or front building.

The organisng model on the other hand sets up organising as an approach that is rather different to traditional union “servicing” and recruitment. The approach of this model is to map workplaces and conduct surveys to find out what issues the workers there are most concerned about. An issue is then selected and a campaign run to get a victory. Through building by starting small and working up the self confidence of the workers and the standing of the union can be steadily improved.

What’s more the organising model can be far more confrontational than the servicing/recruitment approach, with strikes (such as the successful Sodexo workers strike resulting from UNISON’s attempt to implement the model) a fairly common tactic to gain results. With such demonstrable effectiveness and the possibility for militant outcomes you’d think the far left would be raving about this new approach, yet the far left has virtually nothing to say on this new methodology.

This is in part the fault of the far left for not taking sufficient interest in workplace issues. Such an attitude has left as the sole champions of organising certain factions with the union bureaucracies and consequently a conservative vision and practice of organising dominates. Whilst using militant tactics might be a great way to force reluctant employers to recognise your union and to build your membership numbers, once you’ve done a deal with that employer you don’t want pesky members messing it up by trying to win more.

In order to prevent this being the reality of organsing the left needs to engage with and learn this new model. Of course as many lefties will point out large elements of the model aren’t new, they’re a historical rediscovery of how unions used to work. This is only part of the picture though, old-school militancy has been complemented by modern organising techniques, making the organising model a powerful tool.

Union culture

Another incredibly useful tool is that of trade union culture. When the union is the centre-point of cultural and social activities for its members it will be rendered far stronger. After all your much more likely to go down and support the picket line if your mate Bob, who you met through the union football tournament is one of those on strike. The central importance of the union as a social institution was realised by Jim Larkin, who as leader of Ireland’s syndicalist union, the ITGWU, organised union picnics and other cultural activities that greatly contributed to the early successes of this new union.

Another syndicalist union, the CGT in France, used similar tactics. Through its Bourse Du Travail localised structures the union would provide services and a social space to working class communities, building up popular support for the union and encouraging members to socialise together. Sadly such locality based organising is more difficult today as workers in one workplace are unlikely to all live in the same locality, however in spite of this the comrades in the Comités Syndicalistes Révolutionnaires are having some success at reconstructing a local CGT presence.

Whilst on the left we often regret the demise of union clubs and the centrality of unionism in working class life we would do well to head the old socialist adage: don’t mourn, organise! This social infrastructure can be rebuilt, starting small and building up, but it is up to us to ensure that this happens.

If the working class is to stand a chance it must be organised thoroughly to assert its collective power. The techniques of the organsing model and the strengthened social bonds that come through a trade union culture are two vital tools in this task.